Historical perspectives on anti-psychiatry

D B Double

Chapter 2 of Critical psychiatry: The limits of madness

The origin of anti-psychiatry

As mentioned in chapter 1, the origin of the modern use of the term anti-psychiatry was in a book by David Cooper (1967) entitled Psychiatry and anti-psychiatry. In the preface, he talked about anti-psychiatry being at a germinal stage. He suggested that what he called the "institutionalizing processes" and "day-to-day indoctrination" of work in the psychiatric field were starting to produce answers antithetical to conventional solutions.

In particular, he saw schizophrenia as a label applied to people whose acts, statements and experience have been socially invalidated, so that as patients they conform to a passive, inert identity. Psychiatry was therefore seen as reinforcing the alienated needs of society. Cooper was convinced that "the process whereby someone becomes a designated schizophrenic involves a subtle, psychological, mythical, mystical, spiritual violence". This violence commences in the family and is perpetuated in the psychiatric hospital. He even went as far as to suggest that "it is often when people start to become sane that they enter the mental hospital" [his emphasis].

Cooper, therefore, tentatively transformed psychiatry into anti-psychiatry by inverting notions of sanity and insanity. He wanted to create a community in which patients would have the chance to discover and explore authentic relatedness to others. To do this required positive non-action, "an effort to cease interference, to 'lay off' other people and give them and oneself a chance". Being allowed to 'go to pieces' was necessary before one could be helped to come together again. He contrasted his approach with the psychiatric therapeutic community movement pioneered by Maxwell Jones (1952).

He set up Villa 21 in Shenley Hospital between January 1962 and April 1966. An experimental phase of staff withdrawal led to rubbish accumulating in the corridors and dining room tables being covered with the previous days' unwashed plates. Some staff controls were re-introduced with the threat of discharge if patients did not conform to the rules. These apparent limits to institutional change led to the conclusion that a successful unit could only be developed in the community rather than the hospital. Cooper was involved as part of the Philadelphia Association in setting up Kingsley Hall, a 'counterculture' centre in the east end of London (see below under R.D. Laing).

Cooper's theoretical perspective was built on earlier family studies of schizophrenia that attempted to characterise the predominant traits of parents of schizophrenic people. In the initial studies, mothers were seen as characteristically emotionally manipulative, dominating, over-protective and yet at the same time rejecting; fathers were characteristically weak, passive, preoccupied, ill, or, in some other sense 'absent' as an effective parent. In particular, Cooper utilised the theory of Bateson et al (1956) about the role of the double-bind manoeuvre. In this situation, parents convey two or more conflicting and incompatible messages at the same time. As the child is involved in an intense relationship, s/he feels that the communication must be understood but is unable to comment on the inconsistency because it meets with disapproval from the parents. Schizophrenia is, therefore, not to be understood as a disease entity but as a set of person-interactional patterns that require demystification of the confusion of the double-bind.

Families at Villa 21 were studied by participant observation and tape-recording of group situations with families and of the patient in ward groups. Laing & Esterson (1964) used similar techniques. As far as Cooper was concerned, the research succeeded in making the apparently absurd symptoms of schizophrenia intelligible. The results of family orientated therapy with schizophrenics were seen as comparing favourably with those reported for other methods of treatment (Esterson et al, 1965).

The four organisers of the Congress on The Dialectics of Liberation held in London in July 1967 were all identified by Cooper (1968) as anti-psychiatrists. Besides himself, these were R.D. Laing, Joseph Berke and Leon Redler. I want to consider the contributions of each of these people to anti-psychiatry, using them as examples of how it evolved.

Cooper (1967) also made reference to Thomas Szasz (1972) to support the critique of mental illness as a medical disease. R.D. Laing and Szasz are commonly seen as the most important representatives of anti-psychiatry, despite the rejection by both of them of the use of the term of themselves. However, to combine unthinkingly the perspectives of these two authors does not do justice to their major disagreements. We will consider these differences later in the chapter when we discuss the work of Szasz. For the moment, I want to point out that in the origins of anti-psychiatry, Cooper did not apparently notice the differences between Szasz and the other anti-psychiatrists. He seems to have set the trend for neglecting and glossing over this conflict at the heart of anti-psychiatry.

Cooper may have been the first to use the designation 'anti-psychiatry', but some of the concepts that became incorporated into its thinking had been developed before the publication of his book. In particular, R.D. Laing had already published The divided self and Self and others and his study with Aaron Esterson on Sanity, madness and the family. We will turn next to the work of R.D. Laing

R.D. Laing

The basic purpose of Laing's (1960) first book The divided self was to make madness, and the process of going mad, comprehensible. To do this, Laing resorted to the existential tradition in philosophy. He described the schizoid existence of persons split from the world and themselves. This way of being is based on anxiety due to ontological insecurity because of the lack of a strong sense of personal identity. This deficient sense of basic unity leads to the unembodied self, which experiences itself as detached from the body. The body, therefore, becomes felt as part of a false-self system. As far as Laing was concerned, and this may have been the reason for the success of the book, comparatively little had been written about the self that is divided in this way.

Transition to psychosis occurs when these defences fail in their primary purpose of keeping the self alive. The inner self loses any firmly anchored identity and if the veil of the false-self is removed, the individual expresses the 'existential' truth about him/herself in a psychotic matter-of-fact way.

Laing undertook research at the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations and the Tavistock Clinic on interactional processes, especially in marriages and families, with particular but not exclusive reference to psychosis. His second book The self and others (Laing, 1961) was part of the outcome of this research. It is a study of interpersonal relations. An understanding of how an individual acts on others and how others act on him/her is essential for an adequate account of the experience and behaviour of persons. Like Cooper, Laing mentions Bateson's double-bind theory as one way in which a person can be in a false and untenable position. He also shows he was influenced by the paper by Searles (1959) on 'The effort to drive the other person crazy'.

Sanity, madness and the family (Laing & Esterson, 1964) was the result of five years of study of the families of schizophrenics. It is a phenomenological study in the sense that the judgement that the diagnosed patient is behaving in a biologically dysfunctional (hence pathological) way is held in parenthesis. The aim was to establish the social intelligibility of the events in the family that prompted the diagnosis of schizophrenia in one of its members. Unlike The divided self and The self and others, the case histories are allowed to stand for themselves with little elaboration of theory. Esterson (1972) later enriched the details of one of these families in The leaves of spring.

Laing (1967) in The politics of experience and The bird of paradise moved on to describe how humanity is estranged from its authentic possibilities. Schizophrenia is a special strategy that a person creates to live in an unliveable situation. It is a label applied to people as part of a psychiatric ceremonial. For some people, the schizophrenic process may be a natural healing process, but this is generally prevented from happening in our society.

The politics of experience provides a stark, political perspective that was absent from his earlier work. Laing later acknowledged for the later Penguin edition of The divided self that, as far as he was concerned, he did not originally focus enough on social context when attempting to describe individual existence. He became explicit that civilisation represses transcendence and so-called 'normality' is too often an abdication of our true potentialities.

The politics of experience and The bird of paradise was first published by Penguin books. Most of the contents had been published as articles or lectures during 1964/5. The divided self was republished by Penguin in 1965 under the Pelican imprint, and Laing's other books were also eventually republished by Penguin making him a bestseller and cult figure. Laing helped to articulate for the counter-culture the need for the free spirit of the age to escape from the nightmare of the world (Nuttall, 1970).

In 1965 Laing and colleagues founded the Philadelphia Association (PA) as a charity. The PA leased Kingsley Hall, which was the first of several therapeutic community households that it established. Kingsley Hall did not attempt to 'cure' but provided a place where "some may encounter selves long forgotten or distorted" (Schatzman, 1972). The local community was largely hostile to the project. Windows were regularly smashed, faeces pushed through the letter box and residents harassed at local shops. After five years, Kingsley Hall was largely trashed and uninhabitable. Even for Laing, Kingsley Hall was "not a roaring success" (Mullan, 1995).

In March 1971, Laing went to Ceylon, where he spent two months studying meditation in a Buddhist retreat. In India he spent three weeks studying under Gangroti Baba, a Hindu ascetic, who initiated him into the cult of the Hindu goddess Kali. He also spent time learning Sanskrit and visiting Govinda Lama, who had been a guru to Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. For many commentators, this retreat symbolised a lack of commitment to the theory and therapy of mainstream psychiatry (Sedgwick, 1972).

Laing returned the following year and lectured to large audiences as well as engaging in private practice. Knots (Laing, 1970) was another bestseller. It described relational 'knots' or in Laing's words "tangles, fankles, impasses, disjunctions, whirligogs, binds". It was couched in playful, poetic language and was successfully performed on stage.

The politics of the family (Laing, 1971) reinforced the importance of understanding people in social situations. Laing made clear that he was not asserting that families cause schizophrenia. Despite this clear statement, the charge has been repeatedly made. For example, Clare (1997) states:

Many parents of sufferers from schizophrenia cannot forgive him … for adding the guilt of having 'caused' the illness in the first place to their strains and stresses of having to be the main providers of support.

Even if it is true that many parents cannot forgive him, it is obviously wrong and naïve to suggest that he was blaming families. Laing was not talking about conscious, deliberate motivation to cause harm.

The facts of life (Laing, 1976) was a somewhat disjointed book which was not a bestseller. The style included poetic discourse and there was little attempt to provide an overarching theoretical perspective. As Laing himself said, "What is here are sketches of my childhood, first questions, speculations, observations, reflections on conception, intra-uterine life, being born and giving birth …". It seemed at least credible to him that prenatal patterns may be mapped onto natal and postnatal experience. Laing developed 'birthing' as a component of his practice following the technique of Elizabeth Fehr. He thought it more than likely that "many of us are suffering lasting effects from our umbilical cords being cut too soon".

Despite Laing's hopes, this book was not a success and its thematic inconsistencies may be said to have confirmed Sedgwick's (1972) prediction that there was little hope of further developments of Laing's psychiatric framework. As Laing himself said, "I wanted to get into writing again but I couldn't" (Mullan, 1995). Do you love me? (Laing, 1977), Conversations with children (Laing, 1978) and Sonnets (Laing, 1979a) were similar attempts to express a certain sensibility. Conversations with children sold well in translation (Mullan, 1995).

The voice of experience (Laing, 1982) is on the whole better written and probably merits more serious consideration, as Laing himself claimed (Mullan, 1995). Laing discussed the relationship between experience and scientific fact. He reviewed the psychoanalytic literature on psychological life before birth. Laing's themes about intrauterine life are not always easy to follow and the book unfortunately still fails to provide a coherent account of this aspect of his work.

Laing's last published book was his memoir Wisdom, madness and folly (Laing, 1985). It reinforced how mainstream psychiatry tends to avoid the patient as a person. He repeated the disclaimer he had made several times previously about not being an anti-psychiatrist but conceded that he agreed with the anti-psychiatric thesis that "by and large psychiatry functions to exclude and repress those elements society wants excluded and repressed".

Laing's (1987) assessment of his own work can be found in an entry he wrote for The Oxford companion to the mind. He regarded his contribution as operating in a field that can be broadly defined as 'empirical interpersonal phenomenology', which is a branch of social phenomenology. Objective 'Galilean' natural science may not deal adequately with the uncertainty and enigmas of personal interaction. Laing, therefore, thought the main significance of his work may be "what it discloses or reveals of a way of looking which enables what he [Laing] describes to be seen".

David Cooper

After Psychiatry and anti-psychiatry, Cooper (1971) wrote The death of the family. He wanted liberation from the family, which he saw as an ideological conditioning device that reinforces the power of the ruling class in an exploitative society. A commune of people living closely together, either under the same roof or in a more diffused network, was seen as a potential alternative form of micro-social organisation. For Cooper, the meaning of revolution in the first world was a "radical dissolution of false egoic structures in which one is brought up to experience oneself". The urban guerrilla war may need to be fought with molatov cocktails, but spontaneous self-assertion of full personal autonomy should be seen in itself as a decisive act of counterviolence against the system.

As pointed out by Laing, Cooper's form of revolution was a "surreal distillate" (Mullan, 1995). Cooper was a member of the South African Communist Party and was sent to Poland and China to be trained as a professional revolutionary. He never returned to South Africa because he was known by South African intelligence and was frightened he would be killed.

His next book, The grammar of living, made clear that Cooper (1974) was continuing his revolutionary work on self and society. He noted that some of the contents of the book were learnt during periods of incarceration. He viewed The death of the family as largely a revolt against first-world values, but The grammar of living, he thought, merited a rather cooler reception. The blurb on the front cover flap, however, warned that many would still find the book offensive and obscene. Cooper described the conditions for a good voyage on LSD. He argued for liberation of an orgasmic ecstasy and believed that initiation of young children into orgasmic experiences would become part of a full education. In principle he could not exclude sexual relations from therapy. Nor could he ever submit to the gross or subtle injunctions of bourgeois society, by which he meant essentially the classical Marxist conception of the "bourgeoisie being the ruling class in a fully developed capitalist society that rules or rather misrules and exploits through its ownership of the means of production".

In the book, Cooper (1974) made an attempt to define anti-psychiatry. He saw it as reversing the rules of the psychiatric game of labelling and then systematically destroying people by making them obedient robots. The roles of patient and professional in a commune may be abolished through reversal. With the right people, who have themselves been through profound regression, attentive non-interference may open up experience rather than close it down. To go back and relive our lives is natural and necessary and the society that prevents it must be terminated. The subversive nature of anti-psychiatry includes radical sexual liberation. The anti-psychiatrist must give up financial and family security and be prepared to enter his/her own madness, perhaps even to the point of social invalidation. Cooper never hid his zealous fanaticism.

The language of madness (Cooper, 1980) allowed the madman in Cooper to address the madmen in us "in the hope that the former madman speaks clearly or loudly enough for the latter to hear". He talked about the time when he was literally temporarily mad, deluded about being extra-terrestrial and believing that extra-terrestrial beings, appointed from another region in the cosmos, were amongst us. He continued to express his view that madness is the "destructuring of the alienated structures of existence and the restructuring of a less alienated way of being". His theme of 'orgasmic politics' was repeated, not so much to emphasis biological aspects as did Wilhelm Reich, but to see orgasm in revolutionary, political terms. As far as he was concerned, non-psychiatry was coming into being. By this he meant that "'mad' behaviour is to be contained, incorporated in and diffused though the whole society as a subversive source of creativity, spontaneity, not 'disease'". This state of non-psychiatry without mental illness or psychiatry could only be reached in a transformed, genuinely socialist society.

Laing's comment on the work of Cooper is pertinent: "I [Laing] never found anything that he [Cooper] wrote of any particular use to me; in fact, I found it a bit embarrassing" (Mullan, 1995). Although Laing & Cooper (1964) wrote an exposition together in english of Sartrean terms related to dialectical rationality, they were independent characters. Laing enjoyed Cooper's state of mind, but he repeatedly denied he was an 'anti-psychiatrist', hence distancing himself from Cooper's excesses. Esterson (1976), too, made clear that, as far as he was concerned, Sanity, madness and the family was not an anti-psychiatric text. In fact, he saw anti-psychiatry, by which he meant the writings of Cooper and also of Laing, to the extent that he went along with Cooper, as a movement that had done enormous damage to the struggle against coercive, traditional psychiatry.

Cooper's excursion into family, sexual and revolutionary politics could be said to detract from his criticism of psychiatry. However, this critique continued to underpin his writings and was restated in a speech entitled 'What is schizophrenia?' to the Japanese Congress of Neurology and Psychiatry in Tokyo, May 1975, published as an appendix to The language of madness. As far as Cooper was concerned, schizophrenia does not exist as a disease-entity in the ordinary medico-nosological sense. However, madness does exist and deviant behaviour that becomes sufficiently incomprehensible becomes stigmatised as schizophrenia. Here Cooper seems to build on the standard notion of psychosis as 'un-understandable' (Jaspers, 1963), at least for the social process of identification of mental illness, even though he personally thinks it is misguided to pathologise such behaviour. Following Foucault (1965), Cooper saw madness as only excluded from society after the European renaissance, controlled on behalf of the new bourgeois state. Schizophrenia must be understood as interpersonal. It, therefore, has a semantic reality even if it does not exist as a nosological entity. It is also the label for a certain social role.

Joseph Berke

Joseph Berke is an American physician who came to the UK to work with R.D. Laing. Initially he spent time at Dingleton hospital in Scotland with Maxwell Jones. At Kingsley Hall, he was involved with Mary Barnes, who became a celebrated case of the potential for psychosis to be a state in which the self renews itself. The book Mary Barnes. Two accounts of a journey through madness (Barnes & Berke, 1971) describes, from the point of view of both authors, Mary's disintegration into infantile behaviour and her reintegration as a creative adult. Although Barnes was Berke's patient, Laing (1972) did use Mary Barnes as an example of the merits of regression.

Berke may not have made an original contribution to anti-psychiatry but his writings (such as Butterfly man, Berke 1977) reiterated its main themes. The purpose of Butterfly man was to demonstrate the potentially abusive nature of psychiatry and to consider alternative strategies. Berke noted that the mainstream psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott seemed to support the thesis that regression and psychosis could be mechanisms of healing and re-adaptation.

After Kingsley Hall, Berke with Morton Schatzmann and others set up the Arbours Association (http://www.arbourscentre.org.uk). The Arbours Crisis Centre provides immediate and intensive psychotherapeutic support for individuals, couples or families threatened by sudden mental and social breakdown. Three resident therapists live at the centre. They are assisted by a resource group of psychiatrists, psychotherapists, psychologists, nurses, social workers and other professionals. People who come to live at the centre are the "guests" of the resident therapists.

There have been changes at the centre over the years. Originally it was run by a small group who offered their services virtually for free. Now it is registered by the local authorities and funded by social services and health authorities in the NHS health and social care internal market. One of the main functions initially was to provide an alternative to the traditional psychiatric hospital, seen as repressive and damaging, whereas now the function is more to provide a specialised service based on the therapeutic community model enriched by intensive psychoanalytic psychotherapy (Forti, 2002).

Leon Redler and the Philadelphia Association

Leon Redler also came from the United States to work with Maxwell Jones at Dingleton hospital. He then moved to London to work at Kingsley Hall. He is a practising psychotherapist and also a practitioner of the Alexander Technique, Hatha Yoga and Zen. Although he has not written any significant contribution to anti-psychiatry, he was an apologist for Laing (eg. Redler, 1976). Contact with Laing encouraged Redler's pursuit of Zen and Buddhism (Gans & Redler, 2001).

Redler remained loyal to Laing when Laing eventually left the Philadelphia Association (PA). Part of the reason for the split was Laing's interest in birth and pre-birth experience. Redler became Chair from February 1997 to February 1999, the first to hold that position since it was vacated by Laing in 1981. He has been said to embody the tradition that Laing generated in setting up the PA (Gans & Redler, 2001).

From the beginning, the aim of the Philadelphia Association (PA) (http://www.philadelphia-association.co.uk) was to "change the way the 'facts' of 'mental health' and 'mental illness' are seen" (Cooper, 1994). It has fostered the development of several therapeutic community households in London. Its training courses, although psychoanalytically orientated, built on Laing's interests in social phenomenology and spiritual traditions.

The PA is now a member of the psychoanalytic and psychodynamic section of the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP), as is the Arbours Association. Members of the PA households are encouraged to be in individual psychoanalytic psychotherapy. The cost of staying in the houses has been funded by housing benefit and the social housing maintenance grant, unlike the Arbours Association which charges a fee.

Thomas Szasz

Thomas Szasz has posted a summary statement and manifesto on the website dedicated to his life and work (Thomas S. Szasz Cybercenter for Liberty and Responsibility, 2004, www.szasz.com). This is made up of 6 points:-

Szasz has published many books since his original The myth of mental illness (Szasz, 1972). These books reiterate the themes of the summary manifesto. Alongside these issues, Szasz acknowledges that belief in mental illness as a disease of the brain is a negation of the distinction between persons as social beings and bodies as physical objects. As he himself says, there is something positively bizarre about the modern, reductionist denial of persons (Szasz, 2001). This is reflected in the widespread acceptance of unproven claims of physical causes of mental illness.

As noted earlier, both Cooper and Laing made positive reference to Szasz. This may have been primarily in relation to his anti-reductionist stance. It is clear from the transcript of recorded conversations that Laing made with Bob Mullan (1995) in the two years before he died that Laing was not concerned to work through his differences with Szasz. He was surprised that he was not more of an ally.

Szasz (1976) wrote a scathing critique of anti-psychiatry in The New Review. As he himself said, "Because both the anti-psychiatrists [Laing and colleagues] and I [Szasz] oppose certain aspects of psychiatry, our views are combined and confused, and we are often identified as the common enemies of all of psychiatry". Let's try to disentangle these perspectives.

Szasz is critical of what he sees as Laing's inconsistency. If there is no disease, there should be nothing to treat but the Philadelphia Association, for example, accepts residents into its communities. Szasz called the Philadelphia Association "Laing's attempt to set up his version of the Menninger clinic". Kingsley Hall, though, differs from the Menninger clinic "in much the same way that a flophouse differs from a first-class hotel". Szasz is opposed to involuntary hospitalisation, whereas, as Redler (1976) confirmed in his letter in response to Szasz's article, "most of us [Laing and colleagues] agree that even involuntary hospitalisation has a place". For Szasz, it is 'cant' to suggest that the madman is sane and that society is insane, if there is no 'sickness' from which one can make the journey to 'health' via regression.

Laing (1979b) did 'get his own back' in a book review in the New Statesmen. He called the argument of Szasz's books a "diatribe". Laing made clear that in his view it is "a perfectly decent activity to seek to cultivate competence in skilful means of helping people whose relations with themselves and others have become an occasion for wretchedness". On the other hand, the implication of Szasz's position is that undeserving or bad, 'ill' people will "simply be left to rot or be punished". Szasz would view such a comment as a 'smear', because although from his point of view 'mental illness' should not be a factor determining whether criminals are imprisoned, he is not proposing prisoners should be treated inhumanely. Recently, Szasz (2004) has again reiterated how he differs from Laing.

The ideological nature of Szasz's libertarian, free-market principles means that, as far as he is concerned, it is evident that individuals have free will and are responsible for their behaviour. As Laing said, there is little attempt to provide an in-depth analysis of the structures of power and knowledge in Szasz's perspective. Instead, Szasz focuses on what he sees as medicine's threat to human liberty. Medical killing in Nazi Germany is seen as an example of paternalistic state protection of incompetent individuals in the interests of health. Doctors did see sterilisation as a therapeutic intervention to alleviate individual suffering (Braslow, 1997). Szasz sees the modern therapeutic state as infused by the same paternalistic ideology, in particular in relation to involuntary hospitalisation and the insanity defence.

Psychiatry and its critics

Anti-psychiatry has perhaps been defined more by the reaction of mainstream psychiatry than the protagonists themselves. This is reflected in the disavowals of the term, as already mentioned several times in the previous chapter and in this chapter, by the people seen as its main exponents, such as Laing and Szasz.

Sir Martin Roth (1973), when he was the first president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, identified an international movement against psychiatry that he regarded as "anti-medical, anti-therapeutic, anti-institutional and anti-scientific". Clearly mainstream psychiatry, using Roth as an example, felt on the defensive about anti-psychiatry. We will look at this aspect further when considering the response of psychiatry, particularly American psychiatry, to the critique of psychiatric diagnosis that arose out of social labelling theory. At this point, it may also be worth noting that Roth's wholesale portrayal of criticism of psychiatry as little less than an abdication of reason and humanity may better be understood as a clash of different paradigms about how to practice psychiatry (Ingleby, 2004). I want also to return to this theme when discussing the nature of the essence of anti-psychiatry in conclusion.

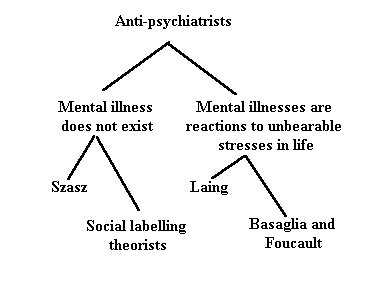

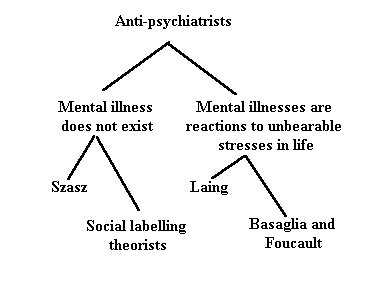

We have already noted the diversity of views collected together under the umbrella of anti-psychiatry, particularly the altercation between Laing and Szasz. Roth & Kroll (1976) elaborated the different groupings into four (see figure).

Figure

The main dividing line is between those that argue that there is no such thing as mental illness, and those that say that mental illnesses are not diseases in the medical sense, but are reactions to unbearable stresses in life. This split is illustrated in the debate between Laing and Szasz. The first group can be further subdivided into those that state that mental illness does not exist in a primary sense, or in the words of Thomas Szasz (1972), who is the main proponent of this group, that 'mental illness is a myth'. The other subdivision would be those identified as social labelling theorists (eg. Thomas Scheff, 1999) who suggest that mental illness does not exist in the sense that it is merely the secondary consequence of identification by others in society. Further discussion about the social labelling perspective follows below.

The group who recognise that the use of the term mental illness is metaphorical and, thereby, do not want to minimise the suffering of people with mental health problems can also be subdivided into two. The first would include Laing, who emphasises that reactions identified as mental illness relate to interpersonal behaviour, particularly within the family. The second subdivision, containing authors like Franco Basaglia (Scheper-Hughes & Lovell, 1987) and Michel Foucault (1965), emphasise that broader societal factors rather than the family are involved in presentations of mental illness. Again, I want to look more closely at the contribution of Basaglia in the next section. I will also return to mention Foucault in the conclusion. Foucault's (1965) historical study of the conceptualisation of madness and, in particular, the isolation of madness in the great confinement in the madhouse in the 17th and 18th centuries, is included in anti-psychiatry because he views the reason of the Enlightenment as oppressive.

For reasons of space, this chapter cannot be comprehensive about the history of anti-psychiatry, and, in particular, cannot do justice to the international perspective noted by Roth (1973). For example, so-called French anti-psychiatry (Turkle, 2004) has been particularly identified with the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1977). Anti-oedipus was these authors' provocative critique of discourses and institutions that repress desire. Another example would be Frantz Fanon, who was head of the psychiatry department at the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria in 1953, and later joined the Algerian National Liberation struggle, becoming a leader in the struggle against racism and for national liberation. Also worthy of mention, as noted in chapter 1, is the book Not made of wood by Jan Foudraine (1974). Foudraine could be seen as the Dutch counterpart of R.D. Laing and contributes a chapter himself to this book (chapter 3).

Franco Basaglia and Psichiatria Democratica

Franco Basaglia worked at the University of Padua for 14 years before leaving to direct the asylum at Gorizia. There he was struck by the effects of institutionalisation (Basaglia, 1964), which Russell Barton (1959) had termed 'institutional neurosis'. He began his anti-institutional struggle to abolish the asylum. Paid work was introduced for patients to avoid exploitation. At the daily assemblea, everybody had a right to speak his or her mind. This forum became the place for expression of empowerment, collectivisation of responsibility and anti-institutional practice.

Initially Basaglia and other Gorizia colleagues came into contact with Maxwell Jones at Dingleton. Later on Basaglia became disillusioned with such reformist measures. As he understood it, the violence and exclusion that underlies social relations created a necessary political, class-related character to his fight. The asylum did not so much contain madness but rather poverty and misery. As expressed by his wife, with whom he worked closely, the asylum was "a dumping ground for the under-privileged, a place of segregation and destruction where the real nature of social problems was concealed behind the alibi of psychiatric treatment and custody" (Basaglia, 1989).

Basaglia's (1967) first major work, L'istituzione negata (The institution denied) was widely circulated in Italy and abroad. It emphasised that what was required was a negation of the system: "an institutional and scientific reversal that leads to the rejection of the therapeutic act as the resolution of social conflict". The risk of defining the institution as a therapeutic community, as did Maxwell Jones, is that the oppositional nature of work in the mental health field is forfeited.

Basaglia was influenced by the writings of Antonio Gramsci, a co-founder of the Italian communist party (Mollica, 1985) Health care workers, such as doctors, nurses and students, regarded as 'technicians of practical knowledge', were encouraged to contest their roles and recognise the social and political context of psychiatric problems. The ultimate refusal to be accomplices of the system may be seen in the mass resignation of the doctors at Gorizia because of failure to invest in community services.

Psichiatria Democratica was founded in 1973 and acted as a pressure group. In Italy, voluntary commitment procedures had been non-existent under the earlier 1904 law. The numbers of people in mental hospitals started to decline later than in the UK and USA. However, the population peak was still earlier (1963) than in some other European countries (Goodwin, 1997).

Law 180 was passed by the Italian parliament in May 1978. Basaglia was the principal architect of the new law. It prevented new admissions to existing mental hospitals and decreed a shift of perspective from segregation and control in the asylum to treatment and rehabilitation in society. A maximum of 15 beds was to be provided in Diagnosis and Treatment units in general hospitals.

Evaluation of the implementation of law 180 has been controversial (Ramon, 1989). The law was also a political compromise and could be said to have produced some inconsistencies. For example, locating the Diagnosis and Treatment Units in general hospitals ensures their medicalised character, which may be seen as undermining the 'anti-psychiatric' spirit of democratic psychiatry.

Basaglia worked in Parma from 1969-71 and moved to Trieste in 1971. The services in Trieste became the most important example of the success of democratic psychiatry. Franco Rotelli continued the work after Basaglia left in 1979 to take over psychiatric services in Rome. The first community structures began functioning in Trieste between 1975-77. A network of community mental health centres was eventually established, open 24 hours, with some attached beds, serving meals and providing domiciliary and walk-in services. Rehabilitation activities were developed: including training and recreational facilities; creative workshops; literacy and educational courses; and co-operatives that created jobs and enterprises that could compete on the open market.

Social labelling theory

The labelling perspective was intended largely as a critique of positivist theories of crime. It challenged the idea that there was a separate and distinct group of people who were intrinsically deviant, arguing instead that it was the reactions of others that defined acts as deviant and labelled those responsible (Becker, 1963). A further distinction was made between primary deviance, the initial rule-breaking act, and secondary deviance, the labelled person's response to the problems caused by the social reactions to their initial deviance (Lemert, 1967).

Scheff's (1999) book Being mentally ill is the best-known and most comprehensive application of labelling theory to mental illness. The theory proposes that a stereotyped notion of mental disorder becomes learnt in early childhood and is continually reaffirmed in ordinary social interaction and in the mass media. Labelled deviants may be rewarded by doctors and others for conforming to this idea of how an ill patient ought to behave and are systematically prevented from returning to the non-deviant role once the label has been applied. Labelling is, therefore, seen as an important cause of ongoing residual deviance. Initially, labelling was regarded as the single most important cause of careers of residual deviance but in later editions of the theory it is conceded that it is merely one of the most important causes.

Being mentally ill is of course not the only way of being deviant in society. The essential point of Scheff's theory is that the person recognised as mentally ill is the deviant for which society does not provide an explicit label. Labelling someone as mentally ill is defined by residual rule-breaking.

Scheff's theory is compatible with wider aspects of anti-psychiatry, such as the study of families of schizophrenics by Laing & Esterson (1964) in Sanity, Madness and the Family. For Scheff as much as for R.D. Laing, the label is a social event and the social event a political act.

Labelling theory has been challenged for several reasons. These include the relative neglect of 'primary deviance', the process of becoming deviant in the first place, and the said lack of evidence for the idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy or a career of deviancy. In particular, Gove (1980) has suggested that the evidence for labelling theory is so overwhelmingly negative that it should be abandoned. At the time that Gove first stated his criticisms, Scheff engaged with them combatively, but he now contents himself with pointing to such supporting evidence as Link & Cullen (1990) and admitting that the evidence for his theory is still sparse and mixed.

Although Scheff, now recognises some excesses of his original theory, it did act as support for the view that mental illness is primarily of social origin. Scheff argues that the statement of a countertheory to the dominant biopsychiatric model, even if not totally valid, is worthwhile in itself. If only for this reason, his book became part of the identified corpus of anti-psychiatric writings.

The other study from a social labelling perspective that was seen as a major threat to mainstream psychiatry was by Rosenhan (1973) 'On being sane in insane places'. What Rosenhan did, in a classic study, was to arrange for his accomplices to be admitted to psychiatric hospital, each with a single complaint of hearing voices that said 'empty', 'hollow' or 'thud'. The auditory hallucinations were reported to be of three weeks duration and that they troubled the person greatly. Beyond alleging the symptoms and falsifying name, vocation and employment, no further alterations of person, history or circumstances were made. On admission to the psychiatric ward, each 'pseudopatient' stopped simulating any symptom of abnormality.

All pseudopatients received a psychiatric diagnosis: 11 were discharged with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, one with a diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis. Eight of the pseudopatients were regarded as 'in remission', one as 'asymptomatic' and three as 'improved'. Length of hospitalisation ranged from 7 to 52 days, with an average of 19 days.

When the results of the study were met with disbelief, Rosenhan informed the staff of a research and teaching hospital that at some time during the following three months, one or more pseudopatients would attempt to be admitted. No such attempt was actually made. Yet approximately 10% of 193 real patients were suspected by two or more staff members to be pseudopatients.

Rosenhan's conclusion was that professionals are unable to distinguish the sane from the insane. He maintained that psychiatric diagnosis is subjective and does not reflect inherent patient characteristics. As far as he was concerned, the pseudopatients had acquired a psychiatric label that sticks as a mark of inadequacy forever.

Robert Spitzer was chair of the Task Force that produced a major revision of the American Psychiatric Association's (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III). Spitzer (1976) was also one of the main critics in the literature of Rosenhan's study and its conclusion. He was so panicked that psychiatric diagnoses may be unreliable that he made every effort to ensure that they were clearly defined (Spitzer & Fleiss, 1974). Although careful analysis of the evidence presented in reliability studies of psychiatric diagnosis may not be as negative as is commonly assumed, the commitment to increase diagnostic reliability became a goal in itself (Blashfield, 1984). Transparent rules were laid down for making each psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-III. The motivation for developing such operational criteria may have initially been to provide consistency in research (Feighner et al, 1972), but the attack from labelling theory reinforced the clinical need for reliable criteria.

This movement in classification has been called neo-Kraepelinian (Klerman 1978), as it promotes many of the ideas of Emil Kraepelin, often regarded as the founder of modern psychiatry. It reinforced a scientific, biological perspective in psychiatry. The neo-Kraepelinian approach, and perhaps DSM-III in particular, provided a justification for mainstream psychiatry to re-establish the reality of mental illness, seen as under threat from labelling theory and anti-psychiatry in general. Such an approach has assumed an orthodox position in modern mental health practice and challenges to the biomedical model now tend to be dismissed as 'anti-psychiatry' (Double, 2002).

Against psychopathology

I want to make clear that although, in some ways, anti-psychiatry was merely a restatement of an interpretative paradigm of mental illness (Ingleby, 2004), its aspirations were not merely to replace the biomedical model with a biopsychological approach (see chapter 11). For example, David Cooper (1980) wrote:

I'm certainly not going to argue a case for a social or socio-psychological aetiology of schizophrenia as opposed to an organic one, or as part of a complex aetiology involving all factors to a varying extent. That would be a futile game if it were all centred on an 'entity' that did not exist in the first place. (p154).

Similarly, R.D. Laing, at times, may have quoted favourably from such psychologically-minded psychiatrists as Manfred Bleuler. However, there is a sense in which Laing wished to go a step further and to "abandon the metaphor of pathology" (Mullan 1995: p275). Or, as he also put it:

… all possible states of mind have to be regarded in the same way in order to diagnose any of them. Normal is as much a diagnosis as abnormal. The persistent, unremitting application of this one point of view year in and year out has its hazards for the psychiatrists." (Laing, 1982: p48)

This abandonment of psychopathology is tied to acknowledgement of psychiatry as a social practice. The debate then becomes one about the social power and legitimacy of psychiatric practice. The close tie between social maladjustment and mental illness creates an unease that motivates anti-psychiatry, at least the Laingian version, to propose an alternative paradigm. Or, as Laing (1985) put it in his autobiography:

I began to dream of trying out a whole new approach without exclusion, segregation, seclusion, observation, control, repression, regimentation, excommunication, invalidation, hospitalization … and so on: without those features of psychiatric practice that seemed to belong to the sphere of social power and structure rather than to medical therapeutics.

At times, this position created a dilemma for Laing, as he sought the endorsement of the psychiatric profession, demonstrated, for example, in his wish to be professor of psychiatry in Glasgow towards the end of his life (Mullan, 1995). For Berke and Redler, to different degrees, and essentially for Laing, the solution was to operate within psychotherapy, a voluntary practice outside the coercion of the Mental Health Act. Basgalia, by contrast, fully accepted the social nature of psychiatric practice within mental health law, stayed within it and altered it.

Relinquishing the notion of pathology may be seen as the essential feature of anti-psychiatry, as it is integral to the positions described in this chapter, albeit to varying degrees. It is what combines such opposing perspectives as those of Laing and Szasz. For example, Szasz suggests what is identified as 'mental illness' is better described as 'problems in living'. Laing and Szasz use different reasoning to arrive at the same conclusion about the invalidity of the notion of mental pathology.

If this rejection of psychopathology is what defines anti-psychiatry, it may be precisely in this area that anti-psychiatry could be said to have failed. Psychiatry is inevitably a social practice. The notion of mental illness is defined by psychological rather than physical dysfunction. (Farrell, 1979). Like Szasz, biomedical psychiatry identifies pathology with physical lesion. The error is to speculate beyond the evidence about the physical basis of mental dysfunction. Anti-psychiatry served a purpose in its critique of biomedical psychiatry, but may have gone too far in its abandonment of the notion of mental pathology altogether.

The essence of anti-psychiatry

In conclusion, I want to say a little more about what integrates the different anti-psychiatrists. The word 'anti-psychiatry' is not without meaning, but it does seem difficult to define precisely. Anti-psychiatry tends to be seen as a passing phase in the history of psychiatry (Tantam, 1991). In this sense it was an aberration, a discontinuity with the proper course of psychiatry. However, it is difficult to accept there was no value in the approach and what may be more beneficial is to look for the continuities, rather than discontinuities, with orthodox psychiatry (Gijswijt-Hofstra & Porter, 1998).

As discussed in the section on 'Psychiatry and its critics', what is clear is that mainstream psychiatry saw anti-psychiatry as a threat. This challenge to the biomedical hypothesis may be the uniting feature of anti-psychiatry. What is not so apparent is why this challenge needs to be seen as 'anti', 'other' and therefore outside psychiatry. After all, the biomedical approach is not the only model or paradigm in psychiatry. For example, the recent critique by Bentall (2003) utilises empirical, cognitive science. Bentall is a clinical psychologist and other mental health professionals may find it easier than psychiatrists to adopt an alternative to the biomedical model. However, although models of mental illness may be used to defend professional roles, they are not intrinsically tied to them. Bentall's book is an attack on mainstream psychiatric practice, and it arises not merely because of his professional allegiance.

Biopsychological and social approaches by psychiatrists themselves have not always been well articulated or appreciated for what they are. For example, the psychobiology of Adolf Meyer (Winters, 1951&2) is commonly criticised for its vague generalities (see chapter 11). Similarly, Arthur Kleinman's (1978) version of social psychiatry may be identified with cross-cultural psychiatry. Its implications, therefore, become restricted to that sphere rather than having a more general impact on mainstream psychiatry.

By contrast, anti-psychiatry stated its critique of biomedical psychiatry in a trenchant manner. As pointed out in the previous section, in fact it tended to go a step further in its opposition to the notion of psychopathology altogether. There was variation in this respect with, for example, some seeing the Italian reform as insufficiently radical because of its tendency to accept the possibility of organic aetiology of mental illness and its willingness to use psychotropic medication. Nonetheless, since the criticisms of anti-psychiatry were first stated, the nature of mental illness has tended to be subsumed under an 'anti-psychiatric' or a 'pro-psychiatric' position.

It seems essential to move beyond this polarisation. Whether this will be better expressed in relation to post-modernism and, in particular, a Foucauldian perspective (Bracken & Thomas, 2001) or a more pragmatic synthesis with psychosocial foundations (Double, 2002) remains to be seen.

Jones (1998) has suggested that objectification of the mentally ill makes psychiatry part of the problem rather than necessarily the solution to mental illness. This may be the essential feature of "the 'anti' element in anti-psychiatry". This notion fits with the interests of the 'anti-psychiatrists' in the negative effects of institutionalisation in the asylums (Goffman, 1961). For example, both Berke and Redler came from the USA to work with Maxwell Jones at Dingleton. Basaglia was also initially interested in this work. Cooper and Laing experimented with therapeutic alternatives to avoid the objectifying nature of the psychiatric hospital. Anti-psychiatry became identified with the closure of the traditional asylum. A constructive outcome of 'anti-psychiatry' could be seen as the therapeutic communities of the Philadelphia Association and the Arbours Crisis Centre.

No doubt anti-psychiatry had its excesses. Ultimately Cooper, and possibly Laing, were more interested in seeking personal liberation than changing psychiatry. Few would want to go as far as Szasz in proposing running a society without specific mental health law. However, the term anti-psychiatry clearly covers more than these immoderate aspects. An historical analysis, of which this chapter is intended to be a part, should help to create a more reasonable evaluation of its merits.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

Barnes, M & Berke, J. (1971) Mary Barnes. Two accounts of a journey through madness. London: MacGibbon and Kee

Barton, R. (1959) Institutional neurosis. Bristol: Wright

Basaglia, F. (1964) The destruction of the mental hospital as a place of institionalisation. http://www.triestesalutementale.it/inglese/allegati/FBASAGLIA1964.pdf (accessed 19 June 2004)

Basaglia, F. (1967) L'istituzione negata. Turin: Einaudi

Basaglia, F.O. (1979) The psychiatric reform in Italy: Summing up and looking ahead. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 35: 90-97

Bateson, G., Jackson, D.D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J. (1956) Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, 1: 251-264

Becker, H.S. (1963) Outsiders. New York: Free Press

Bentall, R. (2003) Madness explained: Psychosis and human nature. London: Allen Lane

Berke, J.H. (1977) Butterfly man. Madness, degradation and redemption. London: Hutchinson

Blashfield, R.K. (1984) The classification of psychopathology. Neo-Kraepelinian and quantitative approaches. New York: Plenum

Bracken, P. & Thomas, P. (2001) Post-psychiatry: a new direction for mental health. BMJ, 322: 724-727

Braslow, J. (1997) Mental ills and bodily cures. London: University of California Press.

Clare, A. (1997) in B. Mullan (ed) R.D. Laing: Creative destroyer. London: Cassell

Cooper, D. (1967) Psychiatry and anti-psychiatry. London: Tavistock

Cooper, D. (1968) (ed.) The dialectics of liberation. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Cooper, D. (1971) The death of the family. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Cooper, D. (1974) The grammar of living. London: Allen Lane

Cooper, D. (1980) The language of madness. Harmondsworth: Pelican

Cooper, R. (1994) (with S. Gans, J.M. Heaton, H. Oakley & P. Zeal) Beginnings. In: R. Cooper, J. Friedman, S. Gans, J.M. Heaton, C. Oakley, H. Oakley & P. Zeal Threholds between philosophy and psychoanalysis. London: Free Association Books

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F (1977) Anti-oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. New York: Viking

Double, D.B. (2002) The limits of psychiatry. BMJ, 324: 900-904

Esterson, A. (1972) The leaves of spring. Harmondsworth: Pelican

Esterson, A. (1976) Anti-psychiatry. [Letter] The New Review, 3: 70-1

Esterson, A., Cooper, D.G. & Laing, R.D. (1965) Results of family orientated schizophrenics with hospitalised schizophrenics. British Medical Journal, 5476: 1462-5

Farrell B A (1979) Mental illness: a conceptual analysis. Psychological Medicine, 9: 21-35.

Feighner, J.P., Robins, E., Guze, S.B., Woodruff, R.A., Winokur, G. & Munoz, R. (1972) Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Archives of General Psychiatry, 26: 57-63.

Foucault, M. (1965) Madness and civilisation. New York: Pantheon Books

Forti, L. (2002) Then and now. In: J.H. Berke, M. Fagan, G. Mak-Pearce & S. Pierides-Mueller (eds) Beyond madness: PsychoSocial interventions in psychosis. London: Jessica Kingsley

Foudraine, J. (1974) Not made of wood: A psychiatrist discovers his own profession London: Quartet Books

Gans, S. & Redler, L. (2001) (in conversation with B. Mullan) Just listening. Philadelphia: Xlibris Corporation

Gijswijt-Hofstra M & Porter R (1998) (eds) Cultures of psychiatry and mental health care in post-war Britain and Netherlands. Amsterdam: Clio Medica

Goffman, E. (1961) Asylums. Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Goodwin S. (1997) Comparative mental health policy: From institutional to community care. London: Sage

Gove, W. (1980) (ed) The labelling of deviance. London: sSage

Ingleby, D. (2004) (ed) Critical psychiatry. The politics of mental health. (Second impression) London: Free Association Books

Jaspers, K. (1963). General psychopathology. (Trans J. Hoenig & M. W. Hamilton). Manchester: Manchester University Press

Jones, C. (1998) Raising the anti: Jan Foudraine, Ronald Laing and anti-psychiatry. In: M. Gijswijt-Hofstra & R. Porter. Cultures of psychiatry. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi (pp. 283-294)

Jones, M. (1952) Social psychiatry. London: Tavistock

Kleinman, A. (1988) Rethinking psychiatry. From cultural cateogory to personal experience. New York: Free Press

Klerman G L (1978) The evolution of a scientific nosology. In J.C. Shershow (ed) Schizophrenia: Science and Practice Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press

Laing, R.D. (1960) The divided self. London: Tavistock

Laing, R.D. (1961) The self and others. London: Tavistock

Laing, R.D. (1967) The politics of experience and The bird of paradise. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Laing, R.D. (1970) Knots. London: Tavistock

Laing, R.D. (1971) The politics of the family and other essays. London: Tavistock

Laing, R.D. (1972) Metanoia: Some experiences at Kingsley Hall, London. In: H.M. Ruitenbeek (ed) Going crazy. The radical therapy of R.D. Laing and others. New York: Bantam

Laing, R.D. (1976) The facts of life. London: Allen Lane

Laing, R.D (1977) Do you love me? London: Allen Lane

Laing, R.D. (1978) Conversations with children. London: Allen Lane

Laing, R.D. (1979a) Sonnets. London: Joseph

Laing, R.D. (1979b) Round the bend. (Review of The theology of medicine, The myth of psychotherapy and Schizophrenia by T.S. Szasz). New Statesman, July 20

Laing, R.D. (1982) The voice of experience. London: Allen Lane

Laing, R.D. (1985) Wisdom, madness and folly. London: Macmillan

Laing, R.D. (1987) Laing's understanding of interpersonal experience. In: R.L. Gregory (ed) (assisted by O.L. Zangwill) The Oxford companion to the mind. Oxford: OUP

Laing, R.D. & Cooper D.G. (1964) Reason and violence. London: Tavistock

Laing, R.D. & Esterson, A. (1964) Sanity, madness and the family. Volume 1. Families of schizophrenics. London: Tavistock

Lemert, E.M. (1967) Human deviance, social problems and social control. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall

Link, B. & Cullen, F. (1990) The labeling theory of mental disorder: A review of the evidence. Research in community and mental health, 6: 75-105

Mollica, R.F. (1985) From Antonio Gramsci to Franco Basaglia: The theory and practice of the Italian psychiatric reform. International Journal of Mental Health, 14: 22-41

Mullan, B. (1995) Mad to be normal. Conversations with R.D. Laing. London: Free Association

Nuttall, J. (1970) Bomb culture. London: Paladin

Redler, L. (1976) Anti-psychiatry. [Letter] The New Review, 3: 71-2

Ramon, S. (1989) The impact of the Italian psychiatric reforms on North American and British professionals. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 35: 120-7

Rosenhan, D.L. (1973) On being sane in insane places. Science, 179: 250-8

Roth, M. (1973) Psychiatry and its critics. British Journal of Psychiatry, 122: 373-8

Roth, M. & Kroll, J. (1986). The reality of mental illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Schatzman, M. (1972) Madness and morals. In: R. Boyers & R. Orrill. (eds) Laing and anti-psychiatry. Harmondsworth: Penguin

Scheff, T.J. (1999) Being mentally ill: A sociological theory. (Third edition). New York: Aldine de Gruyter

Scheper-Hughes, N. & Lovell, A.M. (1987) (eds) Psychiatry inside out: Selected writings of Franco Basaglia. New York: Columbia University Press

Searles, H.F. (1959) The effort to drive the other person crazy; an element in the aetiology and psychotherapy of schizophrenia. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32: 1-18

Sedgwick, P. (1972) R.D. Laing: self, symptom and society. In: R. Boyers & R. Orrill. (eds) Laing and anti-psychiatry. Harmondsorth: Penguin

Spitzer, R.L. (1976) More on pseudoscience in science and the case for psychiatric diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33: 459- 470

Spitzer, R.L. & Fleiss, J.L. (1974) A reanalysis of the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 125: 341-347

Szasz, T.S. (1972) The myth of mental illness. London: Paladin.

Szasz, T.S. (1976) Anti-psychiatry: The paradigm of the plundered mind. The New Review, 3: 3-14

Szasz, T.S. (2001) Pharmacracy. Medicine and Politics in America. London: Praeger

Szasz, T.S. (2004) "Knowing what ain't so": RD Laing and Thomas Szasz. Psychoanalytic Review, 91: 331-346

Tantam, D. (1991) The anti-psychiatry movement. In: G.E. Berrios & H. Freeman (eds). 150 Years of British Psychiatry, 1841-1991. London: Gaskell.

Thomas S. Szasz Cybercenter for Liberty and Responsibility (2004) http://www.szasz.com/ (Accessed June 6, 2004)

Turkle, S. (2004) French anti-psychiatry. In: D. Ingleby (ed) Critical psychiatry: The politics of mental health. London: Free Association Books

Winters E, (1951-2) (ed). The collected papers of Adolf Meyer. (Vols 1-4) Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.